Linux Structure

History

Many events led up to creating the first Linux kernel and, ultimately, the Linux operating system (OS), starting with the Unix operating system's release by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie (whom both worked for AT&T at the time) in 1970. The Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) was released in 1977, but since it contained the Unix code owned by AT&T, a resulting lawsuit limited the development of BSD. Richard Stallman started the GNU project in 1983. His goal was to create a free Unix-like operating system, and part of his work resulted in the GNU General Public License (GPL) being created. Projects by others over the years failed to result in a working, free kernel that would become widely adopted until the creation of the Linux kernel.

At first, Linux was a personal project started in 1991 by a Finnish student named Linus Torvalds. His goal was to create a new, free operating system kernel. Over the years, the Linux kernel has gone from a small number of files written in C under licensing that prohibited commercial distribution to the latest version with over 23 million source code lines (comments excluded), licensed under the GNU General Public License v2.

Linux is available in over 600 distributions (or an operating system based on the Linux kernel and supporting software and libraries). Some of the most popular and well-known being Ubuntu, Debian, Fedora, OpenSUSE, elementary, Manjaro, Gentoo Linux, RedHat, and Linux Mint.

Linux is generally considered more secure than other operating systems, and while it has had many kernel vulnerabilities in the past, it is becoming less and less frequent. It is less susceptible to malware than Windows operating systems and is very frequently updated. Linux is also very stable and generally affords very high performance to the end-user. However, it can be more difficult for beginners and does not have as many hardware drivers as Windows.

Since Linux is free and open-source, the source code can be modified and distributed commercially or non-commercially by anyone. Linux-based operating systems run on servers, mainframes, desktops, embedded systems such as routers, televisions, video game consoles, and more. The overall Android operating system that runs on smartphones and tablets is based on the Linux kernel, and because of this, Linux is the most widely installed operating system.

Linux is an operating system like Windows, iOS, Android, or macOS. An OS is software that manages all of the hardware resources associated with our computer. That means that an OS manages the whole communication between software and hardware. Also, there exist many different distributions (distro). It is like a version of Windows operating systems.

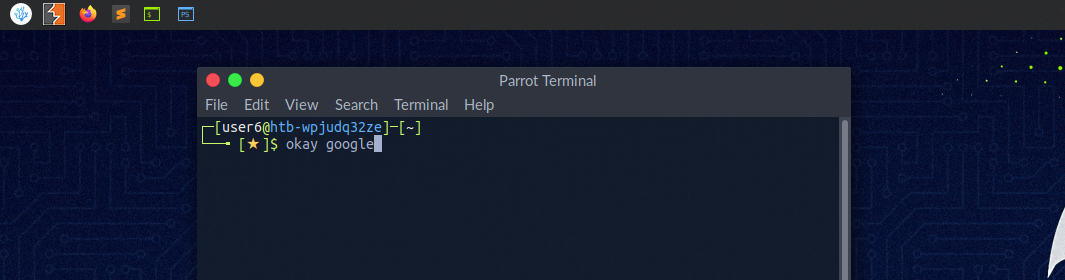

With the interactive instances, we get access to the Pwnbox, a customized version of Parrot OS. This will be the primary OS we will work with through the modules. Parrot OS is a Debian-based Linux distribution that focuses on security, privacy, and development.

Philosophy

Linux follows five core principles:

| Principle | Description |

| Everything is a file | All configuration files for the various services running on the Linux operating system are stored in one or more text files. |

| Small, single-purpose programs | Linux offers many different tools that we will work with, which can be combined to work together. |

| Ability to chain programs together | The integration and combination of different tools enable us to carry out many large and complex tasks, such as processing or filtering specific data results. |

| Avoid captive user interfaces | Linux is designed to work mainly with the shell (or terminal), which gives the user greater control over the operating system. |

| Configuration data stored in a text file | An example of such a file is the /etc/passwd file, which stores all users registered on the system. |

Components

| Component | Description |

| Bootloader | A piece of code that runs to guide the booting process to start the operating system. Parrot Linux uses the GRUB Bootloader. |

| OS Kernel | The kernel is the main component of an operating system. It manages the resources for system's I/O devices at the hardware level. |

| Daemons | Background services are called "daemons" in Linux. Their purpose is to ensure that key functions such as scheduling, printing, and multimedia are working correctly. These small programs load after we booted or log into the computer. |

| OS Shell | The operating system shell or the command language interpreter (also known as the command line) is the interface between the OS and the user. This interface allows the user to tell the OS what to do. The most commonly used shells are Bash, Tcsh/Csh, Ksh, Zsh, and Fish. |

| Graphics server | This provides a graphical sub-system (server) called "X" or "X-server" that allows graphical programs to run locally or remotely on the X-windowing system. |

| Window Manager | Also known as a graphical user interface (GUI). There are many options, including GNOME, KDE, MATE, Unity, and Cinnamon. A desktop environment usually has several applications, including file and web browsers. These allow the user to access and manage the essential and frequently accessed features and services of an operating system. |

| Utilities | Applications or utilities are programs that perform particular functions for the user or another program. |

Linux Architecture

The Linux operating system can be broken down into layers:

| Layer | Description |

| Hardware | Peripheral devices such as the system's RAM, hard drive, CPU, and others. |

| Kernel | The core of the Linux operating system whose function is to virtualize and control common computer hardware resources like CPU, allocated memory, accessed data, and others. The kernel gives each process its own virtual resources and prevents/mitigates conflicts between different processes. |

| Shell | A command-line interface (CLI), also known as a shell that a user can enter commands into to execute the kernel's functions. |

| System Utility | Makes available to the user all of the operating system's functionality. |

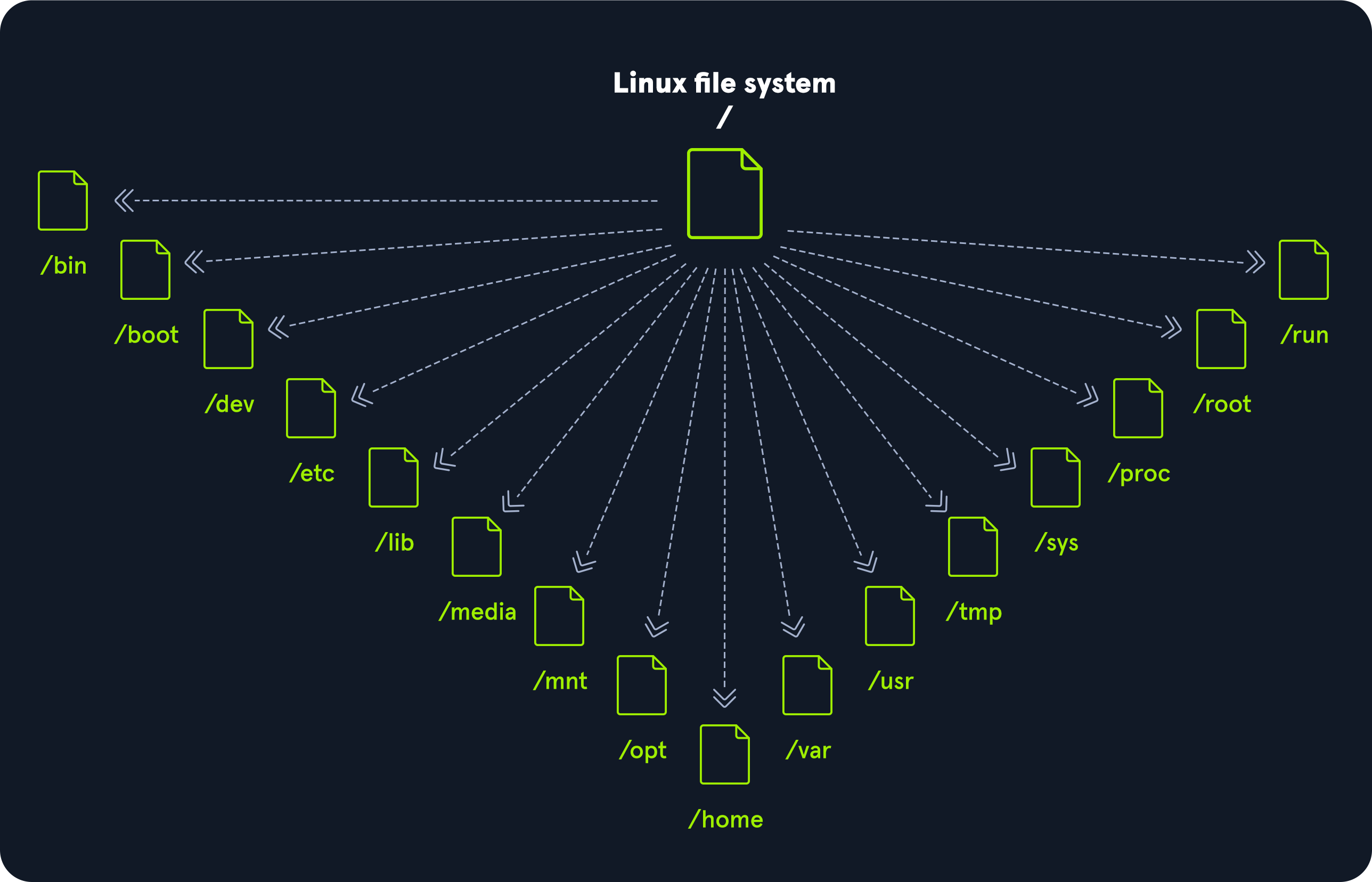

File System Hierarchy

The Linux operating system is structured in a tree-like hierarchy and is documented in the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS). Linux is structured with the following standard top-level directories:

| Path | Description |

| / | The top-level directory is the root filesystem and contains all of the files required to boot the operating system before other filesystems are mounted as well as the files required to boot the other filesystems. After boot, all of the other filesystems are mounted at standard mount points as subdirectories of the root. |

| /bin | Contains essential command binaries. |

| /boot | Consists of the static bootloader, kernel executable, and files required to boot the Linux OS. |

| /dev | Contains device files to facilitate access to every hardware device attached to the system. |

| /etc | Local system configuration files. Configuration files for installed applications may be saved here as well. |

| /home | Each user on the system has a subdirectory here for storage. |

| /lib | Shared library files that are required for system boot. |

| /media | External removable media devices such as USB drives are mounted here. |

| /mnt | Temporary mount point for regular filesystems. |

| /opt | Optional files such as third-party tools can be saved here. |

| /root | The home directory for the root user. |

| /sbin | This directory contains executables used for system administration (binary system files). |

| /tmp | The operating system and many programs use this directory to store temporary files. This directory is generally cleared upon system boot and may be deleted at other times without any warning. |

| /usr | Contains executables, libraries, man files, etc. |

| /var | This directory contains variable data files such as log files, email in-boxes, web application related files, cron files, and more. |

Linux Distributions

Linux Distributions Linux distributions - or distros - are operating systems based on the Linux kernel. They are used for various purposes, from servers and embedded devices to desktop computers and mobile phones. Each Linux distribution is different, with its own set of features, packages, and tools. Some popular examples include:

Ubuntu

Fedora

CentOS

Debian

Red Hat Enterprise Linux

Many users choose Linux for their desktop computers because it is free, open source, and highly customizable. Ubuntu and Fedora are two popular choices for desktop Linux and beginners. It is also widely used as a server operating system because it is secure, stable, and reliable and comes with frequent and regular updates. Finally, we, as cybersecurity specialists, often prefer Linux because it is open source, meaning its source code is available for scrutiny and customization. Because of such customization, we can optimize and customize our Linux distribution the way we want and configure it for specific use cases only if necessary.

We can use those distros everywhere, including (web) servers, mobile devices, embedded systems, cloud computing, and desktop computing. For cyber security specialists, some of the most popular Linux distributions are but are not limited to:

ParrotOS > Ubuntu > Debian Raspberry Pi OS > CentOS > BackBox BlackArch > Pentoo

The main differences between the various Linux distributions are the included packages, the user interface, and the tools available. Kali Linux is the most popular distribution for cyber security specialists, including a wide range of security-focused tools and packages. Ubuntu is widespread for desktop users, while Debian is popular for servers and embedded systems. Finally, red Hat Enterprise Linux and CentOS are popular for enterprise-level computing.

Debian Debian is a widely used and well-respected Linux distribution known for its stability and reliability. It is used for various purposes, including desktop computing, servers, and embedded system. It uses an Advanced Package Tool (apt) package management system to handle software updates and security patches. The package management system helps keep the system up-to-date and secure by automatically downloading and installing security updates as soon as they are available. This can be executed manually or set up automatically.

Debian can have a steeper learning curve than other distributions, but it is widely regarded as one of the most flexible and customizable Linux distros. The configuration and setup can be complex, but it also provides excellent control over the system, which can be good for advanced users. The more control we have over a Linux system, the more complex it feels to become. However, it just feels that way compared to the options and possibilities we get. Without learning it with the required depth, we might spend way more time configuring “easy” tasks and processes than when we would learn to use a few commands and tools more in-depth. We will see it in the Filter Contents and Find Files and Directories sections.

Stability and reliability are key strengths of Debian. The distribution is known for its long-term support releases, which can provide updates and security patches for up to five years. This can be especially important for servers and other systems that must be up and running 24/7. It has had some vulnerabilities, but the development community has quickly released patches and security updates. In addition, Debian has a strong commitment to security and privacy, and the distribution has a well-established security track record. Debian is a versatile and reliable Linux distribution that is widely used for a range of purposes. Its stability, reliability, and commitment to security make it an attractive choice for various use cases, including cyber security.

Introduction to Shell

Introduction to Shell It is crucial to learn how to use the Linux shell, as there are many servers based on Linux. These are often used because Linux is less error-prone as opposed to Windows servers. For example, web servers are often based on Linux. Knowing how to use the operating system to control it effectively requires understanding and mastering Linux’s essential part, the Shell. When we first switched from Windows to Linux, does it look something like this:

A Linux terminal, also called a shell or command line, provides a text-based input/output (I/O) interface between users and the kernel for a computer system. The term console is also typical but does not refer to a window but a screen in text mode. In the terminal window, commands can be executed to control the system.

We can think of a shell as a text-based GUI in which we enter commands to perform actions like navigating to other directories, working with files, and obtaining information from the system but with way more capabilities.

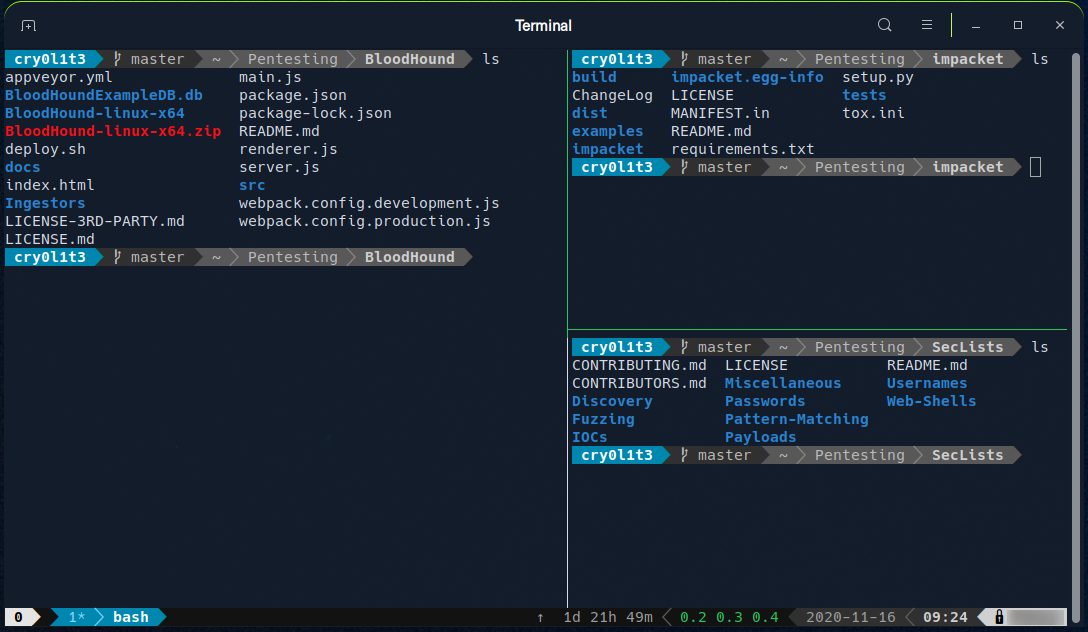

Terminal Emulators Terminal emulation is software that emulates the function of a terminal. It allows the use of text-based programs within a graphical user interface (GUI). There are also so-called command-line interfaces (CLI) that run as additional terminals in one terminal. In short, a terminal serves as an interface to the shell interpreter.

Terminal emulators and multiplexers are beneficial extensions for the terminal. They provide us with different methods and functions to work with the terminal, such as splitting the terminal into one window, working in multiple directories, creating different workspaces, and much more. An example of the use of such a multiplexer called Tmux could look something like this:

Shell The most commonly used shell in Linux is the Bourne-Again Shell (BASH), and is part of the GNU project. Everything we do through the GUI we can do with the shell. The shell gives us many more possibilities to interact with programs and processes to get information faster. Besides, many processes can be easily automated with smaller or larger scripts that make manual work much easier.

Besides Bash, there also exist other shells like Tcsh/Csh, Ksh, Zsh, Fish shell and others.

Prompt Description

Prompt Description The bash prompt is easy to understand and, by default, includes information such as the user, hostname, and current working directory. It is a string of characters displayed on the terminal screen that indicates that the system is ready for our input. It typically includes information such as the current user, the computer’s hostname, and the current working directory. The prompt is usually displayed on a new line, and the cursor is positioned after the prompt, ready for the user to start typing a command.

It can be customized to provide useful information to the user. The format can look something like this: Prompt Description

<username>@<hostname><current working directory>$

The home directory for a user is marked with a tilde <~> and is the default folder when we log in. Prompt Description

The dollar sign, in this case, stands for a user. As soon as we log in as root, the character changes to a hash <#> and looks like this: Prompt Description

root@htb[/htb]#

For example, when we upload and run a shell on the target system, we may not see the username, hostname, and current working directory. This may be due to the PS1 variable in the environment not being set correctly. In this case, we would see the following prompts:

- Unprivileged - User Shell Prompt Prompt Description

$

- Privileged - Root Shell Prompt Prompt Description

#

In addition to providing basic information like the current user and working directory, we can customize to display other information in the prompt, such as the IP address, date, time, the exit status of the last command, and more. This is especially useful for us during our penetration tests because we can use various tools and possibilities like script or the .bash_history to filter and print all the commands we used and sort them by date and time. For example, the prompt could be set to display the full path of the current working directory instead of just the current directory name, which can also include the target’s IP address if we work organized.

The prompt can be customized using special characters and variables in the shell’s configuration file (.bashrc for the Bash shell). For example, we can use: the \u character to represent the current username, \h for the hostname, and \w for the current working directory.

Special Character Description

\d Date (Mon Feb 6)

\D{%Y-%m-%d} Date (YYYY-MM-DD)

\H Full hostname

\j Number of jobs managed by the shell

\n Newline

\r Carriage return

\s Name of the shell

\t Current time 24-hour (HH:MM:SS)

\T Current time 12-hour (HH:MM:SS)

\@ Current time

\u Current username

\w Full path of the current working directory

Customizing the prompt can be a useful way to make your terminal experience more personalized and efficient. It can also be a helpful tool for troubleshooting and problem-solving, as it can provide important information about the system’s state at any given time.

In addition to customizing the prompt, we can customize their terminal environment with different color schemes, fonts, and other settings to make their work environment more visually appealing and easier to use.

However, we see the same as when working on the Windows GUI here. We are logged in as a user on a computer with a specific name, and we know which directory we are in when we navigate through our system. Bash prompt can also be customized and changed to our own needs. The adjustment of the bash prompt is outside the scope of this module. However, we can look at the bash-prompt-generator and powerline, which gives us the possibility to adapt our prompt to our needs.

Getting Help

Getting Help We will always stumble across tools whose optional parameters we do not know from memory or tools we have never seen before. Therefore it is vital to know how we can help ourselves to get familiar with those tools. The first two ways are the man pages and the help functions. It is always a good idea to familiarize ourselves with the tool we want to try first. We will also learn some possible tricks with some of the tools that we thought were not possible. In the man pages, we will find the detailed manuals with detailed explanations.

Syntax: Getting Help

satvikbash@htb[/htb]$ man <tool>

Let us have a look at an example:

Example:

- Getting Help

satvikbash@htb[/htb]$ man curl

- Getting Help

curl(1) Curl Manual curl(1)

NAME

curl - transfer a URL

SYNOPSIS

curl [options] [URL...]

DESCRIPTION

curl is a tool to transfer data from or to a server, using one of the supported protocols (DICT, FILE, FTP, FTPS, GOPHER, HTTP, HTTPS,

IMAP, IMAPS, LDAP, LDAPS, POP3, POP3S, RTMP, RTSP, SCP, SFTP, SMB, SMBS, SMTP, SMTPS, TELNET, and TFTP). The command is designed to work without user interaction.

curl offers a busload of useful tricks like proxy support, user authentication, FTP upload, HTTP post, SSL connections, cookies, file transfer resume, Metalink, and more. As we will see below, the number of features will make our head spin!

curl is powered by libcurl for all transfer-related features. See libcurl(3) for details.

Manual page curl(1) line 1 (press h for help or q to quit)

After looking at some examples, we can also quickly look at the optional parameters without browsing through the complete documentation. We have several ways to do that.

- Syntax: Getting Help

satvikbash@htb[/htb]$ <tool> --help

- Example: Getting Help

satvikbash@htb[/htb]$ curl --help

Usage: curl [options...] <url>

--abstract-unix-socket <path> Connect via abstract Unix domain socket

--anyauth Pick any authentication method

-a, --append Append to target file when uploading

--basic Use HTTP Basic Authentication

--cacert <file> CA certificate to verify peer against

--capath <dir> CA directory to verify peer against

-E, --cert <certificate[:password]> Client certificate file and password

<SNIP>

We can also use the short version of it:

Syntax: Getting Help

satvikbash@htb[/htb]$ <tool> -h

- Example: Getting Help

satvikbash@htb[/htb]$ curl -h

Usage: curl [options...] <url>

--abstract-unix-socket <path> Connect via abstract Unix domain socket

--anyauth Pick any authentication method

-a, --append Append to target file when uploading

--basic Use HTTP Basic Authentication

--cacert <file> CA certificate to verify peer against

--capath <dir> CA directory to verify peer against

-E, --cert <certificate[:password]> Client certificate file and password

<SNIP>

As we can see, the results from each other do not differ in this example. Another tool that can be useful in the beginning is apropos. Each manual page has a short description available within it. This tool searches the descriptions for instances of a given keyword.

Syntax: Getting Help

satvikbash@htb[/htb]$ apropos <keyword>

- Example: Getting Help

satvikbash@htb[/htb]$ apropos sudo

sudo (8) - execute a command as another user

sudo.conf (5) - configuration for sudo front end

sudo_plugin (8) - Sudo Plugin API

sudo_root (8) - How to run administrative commands

sudoedit (8) - execute a command as another user

sudoers (5) - default sudo security policy plugin

sudoreplay (8) - replay sudo session logs

visudo (8) - edit the sudoers file

Another useful resource to get help if we have issues to understand a long command is: https://explainshell.com/

System Information

Since we will be working with many different Linux systems, we need to learn the structure and the information about the system, its processes, network configurations, users, directories, user settings, and the corresponding parameters. Here is a list of the necessary tools that will help us get the above information. Most of them are installed by default.

| Command | Description |

| whoami | Displays current username. |

| id | Returns users identity |

| hostname | Sets or prints the name of current host system. |

| uname | Prints basic information about the operating system name and system hardware. |

| pwd | Returns working directory name. |

| ifconfig | The ifconfig utility is used to assign or to view an address to a |

| network interface and/or configure network interface parameters. | |

| ip | Ip is a utility to show or manipulate routing, network devices, interfaces and tunnels. |

| netstat | Shows network status. |

| ss | Another utility to investigate sockets. |

| ps | Shows process status. |

| who | Displays who is logged in. |

| env | Prints environment or sets and executes command. |

| lsblk | Lists block devices. |

| lsusb | Lists USB devices |

| lsof | Lists opened files. |

| lspci | Lists PCI devices. |

Let us look at a few examples.

Hostname

The hostname command is pretty self-explanatory and will just print the name of the computer that we are logged into

satvik@htb[/htb]$ hostnamenixfund

Whoami

This quick and easy command can be used on both Windows and Linux systems to get our current username. During a security assessment, we obtain reverse shell access on a host, and one of the first bits of situational awareness we should do is figuring out what user we are running as. From there, we can figure out if the user has any special privileges/access.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ whoamicry0l1t3

Id

The id command expands on the whoami command and prints out our effective group membership and IDs. This can be of interest to penetration testers looking to see what access a user may have and sysadmins looking to audit account permissions and group membership. In this output, the hackthebox group is of interest because it is non-standard, the adm group means that the user can read log files in /var/log and could potentially gain access to sensitive information, membership in the sudo group is of particular interest as this means our user can run some or all commands as the all-powerful root user. Sudo rights could help us escalate privileges or could be a sign to a sysadmin that they may need to audit permissions and group memberships to remove any access that is not required for a given user to carry out their day-to-day tasks.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ iduid=1000(cry0l1t3) gid=1000(cry0l1t3) groups=1000(cry0l1t3),1337(hackthebox),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),116(lpadmin),126(sambashare)

Uname

Let's dig into the uname command a bit more. If we type man uname in our terminal, we will bring up the man page for the command, which will show the possible options we can run with the command and the results.

UNAME(1) User Commands UNAME(1)

NAME

uname - print system information

SYNOPSIS

uname [OPTION]...

DESCRIPTION

Print certain system information. With no OPTION, same as -s.

-a, --all

print all information, in the following order, except omit -p and -i if unknown:

-s, --kernel-name

print the kernel name

-n, --nodename

print the network node hostname

-r, --kernel-release

print the kernel release

-v, --kernel-version

print the kernel version

-m, --machine

print the machine hardware name

-p, --processor

print the processor type (non-portable)

-i, --hardware-platform

print the hardware platform (non-portable)

-o, --operating-system

Running `uname -a` will print all information about the

machine in a specific order: kernel name, hostname, the kernel release,

kernel version, machine hardware name, and operating system. The `-a` flag will omit `-p` (processor type) and `-i` (hardware platform) if they are unknown.

``` bash

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ uname -aLinux box 4.15.0-99-generic #100-Ubuntu SMP Wed Apr 22 20:32:56 UTC 2020 x86_64 x86_64 x86_64 GNU/Linux

</code></pre>

<p>From the above command, we can see that the kernel name is <code>Linux</code>, the hostname is <code>box</code>, the kernel release is <code>4.15.0-99-generic</code>, the kernel version is <code>#100-Ubuntu SMP Wed Apr 22 20:32:56 UTC 2020</code>, and so on. Running any of these options on their own will give us the specific bit output we are interested in.</p>

<h3 id="uname-to-obtain-kernel-release">Uname to Obtain Kernel Release</h3>

<p>Suppose we want to print out the kernel release to search for potential kernel exploits quickly. We can type <code>uname -r</code> to obtain this information.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ uname -r4.15.0-99-generic

</code></pre>

<p>With this info, we could go and search for "4.15.0-99-generic exploit," and the first <a href="https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/47163">result</a> immediately appears useful to us.</p>

<p>It is highly recommended to study the commands and understand what

they are for and what information they can provide. Though a bit

tedious, we can learn much from studying the manpages for common

commands. We may even find out things that we did not even know were

possible with a given command. This information is not only used for

working with Linux. However, it will also be used later to discover

vulnerabilities and misconfigurations on the Linux system that may

contribute to privilege escalation. Here are a few optional exercises

that we can solve for practice purposes, which will help us become

familiar with some of the commands.</p>

<h3 id="logging-in-via-ssh">Logging In via SSH</h3>

<p><code>Secure Shell</code> (<code>SSH</code>) refers to a protocol

that allows clients to access and execute commands or actions on remote

computers. On Linux-based hosts and servers running or another Unix-like

operating system, SSH is one of the permanently installed standard

tools and is the preferred choice for many administrators to configure

and maintain a computer through remote access. It is an older and very

proven protocol that does not require or offer a graphical user

interface (GUI). For this reason, it works very efficiently and occupies

very few resources. We use this type of connection in the following

sections and in most of the other modules to offer the possibility to

try out the learned commands and actions in a safe environment. We can

connect to our targets with the following command:</p>

<h3 id="ssh-login">SSH Login</h3>

<pre><code class="language-bash">satvikbash@htb[/htb]$ ssh [username]@[IP address]

</code></pre>

<h1 id="navigation">Navigation</h1>

<p>Navigation is essential, like working with the mouse as a standard

Windows user. With it, we move across the system and work in directories

and with files, we need and want. Therefore, we use different commands

and tools to print out information about a directory or a file and can

use advanced options to optimize the output to our needs.</p>

<p>One of the best ways to learn something new is to experiment with it.

Here we cover the sections on navigating through Linux, creating,

moving, editing, and deleting files and folders, finding them on the

operating system, different types of redirects, and what file

descriptors are. We will also find shortcuts to make our work with the

shell much easier and more comfortable. We recommend experimenting on

our locally hosted VM. Ensure we have created a snapshot for our VM in

case our system gets unexpectedly damaged.</p>

<p>Let us start with the navigation. Before we move through the system,

we have to find out in which directory we are. We can find out where we

are with the command <code>pwd</code>.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ pwd/home/cry0l1t3

</code></pre>

<p>Only the <code>ls</code> command is needed to list all the contents

inside a directory. It has many additional options that can complement

the display of the content in the current folder.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ lsDesktop Documents Downloads Music Pictures Public Templates Videos

</code></pre>

<p>Using it without any additional options will display the directories and files only. However, we can also add the <code>-l</code> option to display more information on those directories and files.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ ls -ltotal 32

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:37 Desktop

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Documents

drwxr-xr-x 3 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 15 03:26 Downloads

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Music

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Pictures

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Public

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Templates

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Videos

</code></pre>

<p>First, we see the total amount of blocks (<code>512-byte</code>) used

by the files and directories listed in the current directory, which

indicates the total size used. That means it used 32 * 512-byte = <code>16384 bytes</code> of disk space. Next, we see a few columns that are structured as follows:</p>

<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>Column Content</th>

<th>Description</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody><tr>

<td>drwxr-xr-x</td>

<td>Type and permissions</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>2</td>

<td>Number of hard links to the file/directory</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>cry0l1t3</td>

<td>Owner of the file/directory</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>htbacademy</td>

<td>Group owner of the file/directory</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>4096</td>

<td>Size of the file or the number of blocks used to store the directory information</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Nov 13 17:37</td>

<td>Date and time</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Desktop</td>

<td>Directory name</td>

</tr>

</tbody></table>

<p>However, we will not see everything that is in this folder. A

directory can also have hidden files that start with a dot at the

beginning of its name (e.g., <code>.bashrc</code> or <code>.bash_history</code>). Therefore, we need to use the command <code>ls -la</code> to <code>list all</code> files of a directory:</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ ls -latotal 403188

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:37 .bash_history

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:37 .bashrc

...SNIP...

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:37 Desktop

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Documents

drwxr-xr-x 3 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 15 03:26 Downloads

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Music

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Pictures

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Public

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Templates

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Videos

</code></pre>

<p>To list the contents of a directory, we do not necessarily need to navigate there first. We can also use “<code>ls</code>” to specify the path where we want to know the contents.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ ls -l /var/total 52

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mai 15 18:54 backups

drwxr-xr-x 18 root root 4096 Nov 15 16:55 cache

drwxrwsrwt 2 root whoopsie 4096 Jul 25 2018 crash

drwxr-xr-x 66 root root 4096 Mai 15 03:08 lib

drwxrwsr-x 2 root staff 4096 Nov 24 2018 local

<SNIP>

</code></pre>

<p>We can do the same thing to navigate to the directory. To move through the directories, we use the command <code>cd</code>. Let us change to the <code>/dev/shm</code> directory. Of course, we can go to the <code>/dev</code> directory first and then <code>/shm</code>. Nevertheless, we can also enter the full path and jump there.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ cd /dev/shmcry0l1t3@htb[/dev/shm]$

</code></pre>

<p>Since we were in the home directory before, we can quickly jump back to the directory we were last in.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[/dev/shm]$ cd -cry0l1t3@htb[~]$

</code></pre>

<p>The shell also offers us the auto-complete function, which makes navigation easier. If we now type <code>cd /dev/s</code> and press <code>[TAB] twice</code>, we will get all entries starting with the letter “<code>s</code>” in the directory of <code>/dev/</code>.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ cd /dev/s [TAB 2x]shm/ snd/

</code></pre>

<p>If we add the letter “<code>h</code>” to the letter “<code>s</code>,” the shell will complete the input since otherwise there will be no folders in this directory beginning with the letters “<code>sh</code>”. If we now display all contents of the directory, we will only see the following contents.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[/dev/shm]$ ls -la /dev/shmtotal 0

drwxrwxrwt 2 root root 40 Mai 15 18:31 .

drwxr-xr-x 17 root root 4000 Mai 14 20:45 ..

</code></pre>

<p>The first entry with a single dot (<code>.</code>) indicates the current directory we are currently in. The second entry with two dots (<code>..</code>) represents the parent directory <code>/dev</code>. This means we can jump to the parent directory with the following command.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[/dev/shm]$ cd ..cry0l1t3@htb[/dev]$

</code></pre>

<p>Since our shell is filled with some records, we can clean the shell with the command <code>clear</code>. First, however, let us return to the directory <code>/dev/shm</code> before and then execute the <code>clear</code> command to clean up our terminal.</p>

<pre><code class="language-bash">cry0l1t3@htb[/dev]$ cd shm && clear

</code></pre>

<p>Another way to clean up our terminal is to use the shortcut <code>[Ctrl] + [L]</code>. We can also use the arrow keys (<code>↑</code> or <code>↓</code>)

to scroll through the command history, which will show us the commands

that we have used before. But we also can search through the command

history using the shortcut <code>[Ctrl] + [R]</code> and type some of the text that we are looking for.</p>

<p><strong>STAY TUNED</strong> 🧑💻

<strong>CONTENT WILL UPDATE SOON</strong> 😁</p>